By Angelo Zinna

Dive into the compelling world of Kelly Lynn Lunde, a seasoned photojournalist whose lens has captured some of Europe's most turbulent regions. In this detailed exploration, Kelly discusses her initial foray into photography, her impactful work on refugee crises, and the personal toll of documenting humanity's hardest stories. Learn about her courageous journey through the field of photojournalism, her involvement with the WomenPhotograph initiative, and her profound reflections on the challenges that led her to a temporary pause from photography. This article offers an intimate glimpse into the life of a photographer dedicated to telling stories that shape our understanding of the world.

Although Kelly Lynn Lund is not photographing at the moment, she still has a lot to say about the craft of photojournalism. After working as a freelance photographer for the past five years, publishing her stories on major media outlets such as Al Jazeera, Human Rights Watch, Buzzfeed News, Huffington Post, Vice News, and Open Society Foundation, Kelly has taken a break to address the physical consequences of living as a witness of some of the Europe's most problematic regions, we spoke to her about her career as an independent photographer and about life after photojournalism.

How did you get started with photography and how did you enter the world of news media?

I’ve been highly observant and curious for as long as I can remember. I think photography was something that allowed me to express artistically, what was already happening in my mind all the time. I got into it as a teenager and later took photos for my university’s school newspaper. I double majored in history and education and graduated with a teaching degree but knew I wasn’t ready to enter that field any time soon. I had this big, ambiguous dream to do something following my studies but didn’t have a solid idea of what that was. On a bit of whim, I went to the West Bank to do an internship with a small news network in Bethlehem and was immediately surrounded by an abundance of devastating stories in a very accessible journalistic environment. I fell for Palestine pretty quickly and turned down some jobs to stay and then come back again to study Arabic and figure out my life there. It took a long time to believe and call myself a journalist, but I had been photographing and crafting narratives since that first trip.

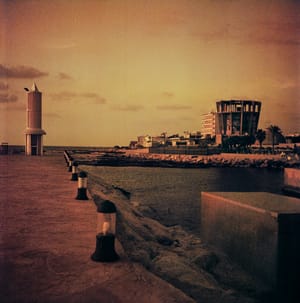

© Kelly Lunde

Much of your work focuses on issues related to displacement in Europe and the Middle East. How did you first get involved in reporting on the refugee crisis? How has your mindset changed since you started?

Looking back, it was relationships that helped center refugee reality at the center of my work and political worldview. During university, I became close with a newly resettled Nepalese family that had been displaced from Bhutan. Over the course of three years, I was intimately exposed to their story and had this compulsion to share it. When I was based in Palestine, I lived in a refugee community that was fiercely proud of their heritage though it came with various forms of additional hardship compounded on top of oppression faced by the whole of the Palestinian population. My main project there became covering the Israeli military’s presence inside the camp, largely because my friends kept getting arrested for ludicrous reasons. I’m not sure if I planned it from the beginning, it’s just where I usually found myself. From there, I was deported by Israeli security and banned for a while so I moved to Amman, Jordan to continue work. I covered Palestinian camps there but also Syrian, Iraqi and Kurdish communities before heading to Lesvos with a colleague. Like anything else, refugee identity is complicated and dependent on a lot of circumstances. I learned to be curious about the spectrum and not expect similar experiences from different people.

You have traveled to refugee camps in Greece and France, telling stories about migration from different perspectives. You show those who arrive, but also those who are trying to help (Le Soccoristas) and the difficulties of living in camps (Eko Camp). Is there an aspect of the refugee crisis that you believe is yet untold? Something that we, the general public, should pay more attention to?

I have a friend on the US border who recently Instagrammed a video of her and a group of migrant/refugees including moms with infants being teargassed. I had a flashback to when I witnessed the same scenario playing out on the border between Greece and Macedonia. People tend to be shocked by these things but they shouldn’t be. This is the status quo for marginalized, dispossessed populations all over the world. The crisis in Europe has died down since the route closed in 2016, but boats continue to arrive and there are overcrowded camps throughout Greece still operating in squalor while the collective mental health of refugee populations deteriorate. Sometimes when people ask me about trauma personally, witnessing the death of people’s dreams is what I think of first. European and US economies absolutely have the capacity to do a better job at taking care of these populations that are trying to start lives in and contribute to nations that have often played roles in destabilizing their native countries. Deportations are also still an active and common threat to thousands in the theoretically safest European country to be - Germany.

What difficulties did you encounter during those assignments? How did the people living in the camps welcome you? Is there an episode that you remember more vividly?

I am still learning how to witness without internalizing. Highlighting disturbing hidden realities is a fundamental component of this work and it can get very tricky without good boundaries. Also, being a woman working alone is sort of dangerous every place I’ve every been. And then there’s the fact that this job is not exactly lucrative.

People tend to be exceedingly gracious, offering their own food rations, openly sharing about their experience and making tea. I’ve been on most of the shittiest stages in this crisis and people always have tea for you. It’s an ironic testament to the cultural value of hospitality in these communities. What stands out? My experience with the Rahimis…an Afghan refugee family often I helped rescue in the Aegean and eventually followed through the Balkan route to Germany. I’ve visited them regularly since. I watched them bury a son on Lesvos and give birth to another in Bonn. They are still waiting for asylum.

As far as I understand, you are taking a break from press reporting to focus on more personal projects. What are the issues in photojournalism today, in your opinion? What made you stop?

Ultimately, I became debilitated by trauma. I started to notice PTSD symptoms in 2016 not long after I moved on from Lesvos. I had endured a lot of sexual harassment and assaults alongside the secondary trauma of witnessing what I have covered. Eventually, I moved home and decided to attempt to address every fiber of emotional and physical pain in my body…to witness it like I had witnessed others and learn how to care for myself. That is an ongoing process that includes unpacking unhelpful paradigms developed in childhood and addressing the way my body has manifested an array of chronic conditions. I am hopeful about seeing increasing awareness around the mental health reality of journalists but also just the world.

And what would you suggest to someone starting out?

Throughout most of my working life, I felt the unconscious need to feel what my subjects were feeling and bear some of that weight. I slowly realized how pointless and devastating that was to myself. To someone starting out in this field, I would say, listen to your body. Develop a real relationship with yourself where your health and wellbeing are ultimately the priority. Take breaks. Get a therapist. Be kind. Resist the urge to be competitive. The more you share and collaborate, oftentimes the more you find yourself surrounded by good-hearted folks who have the same passion as you.

Prepare for rejection. You should be getting rejected all the time if you are a freelancer and pitching enough. Most people either end up behind a desk or being a stringer for an agency. I couldn’t make the compromise myself so I often came home to teach for months here and there to make enough to keep going. I always found time to follow stories and subjects that I was pulled to, whether or not they always fit into an existing piece I was about to publish. The cool thing about photography is that, if you follow your intuition, you can often end up with a body of photographs and a narrative that unfolds itself organically from something you never could have planned for.

Trust what you are drawn to and find ways to always be filling that creative internal bucket. There is not one way to do this work, find your own unique path. Also, if you are a woman in this field, look in the mirror regularly and tell Imposter Syndrome to fuck off. Seriously, do it every day.

What does objectivity mean to you? How do you make sure a story comes across as truthful as possible?

I’d say objectivity is subjective! I have come to terms with my own biases, they inform my stories and can be seen in my body of work. If I quote authorities like the police or most government officials in any context, it’s often to demonstrate inconsistency in their public persona and an attempt to destabilize their perceived role as protectors of peace. It’s common in mainstream media to attempt a balance between traditional power structures and citizen populations. The power imbalance I’ve witnessed first and second hand in the East and West is the reason why my stories rarely posture authorities as legitimate models of leadership. In my experience, it’s factually inaccurate. I spent a lot of early years ruminating on objective truth before realizing that ultimately, I get to craft the story. I guess I value accuracy and integrity over the standard of objectivity so prized in mainstream media.

What is next for you? Where do you see your work going in the future?

I am focusing on my health. My body has changed a lot since I gave it space to feel what I had been repressing. I’m trying to calm my nervous system and achieve a proper balance in all areas of my life. I have branched out artistically in different ways…shooting film, dancing, drawing and writing like I always have. I still follow up with with the Rahimi family and that project will be published at some point. I think I’d like to write a book about that experience and self-publish some poetry. I’d eventually like to do a project checking back in with subjects and friends within the refugee community that are resettled in different places. I work at a Lebanese restaurant to pay the bills and am working to believe my investment in my personal well being is the only way I could continue to tell stories.