By Angelo Zinna

Starting out as a staff photographer for Philippines Graphic, Veejay Villafranca's learned the craft of documentary photography capturing the social issues of his home country. From his base in Manila, however, Villafranca has seen his work published internationally on the pages of The Guardian, Bloomberg, and the International Herald Tribune, among others. As a freelancer, Veejay has worked together with various aid organizations, telling the stories of underprivileged in the Philippines and East Asia. One of his most intriguing projects, “Marked: The Gangs of Baseco,” captures the reality of ex-gang members attempting to find a new identity. We talked to Villafranca about the developments of his work and his future projects.

How did you get started with photography? What is your background?

I applied as a part-time photojournalist in one of the news magazines in Manila (Philippines Graphic). After six months, I became regularized and was assigned to cover national news. Those were my formative years in the industry, honing both my photography and journalistic skillset. After almost five years I left and pursued documentary photography with a stern focus on the Philippines and Asia.

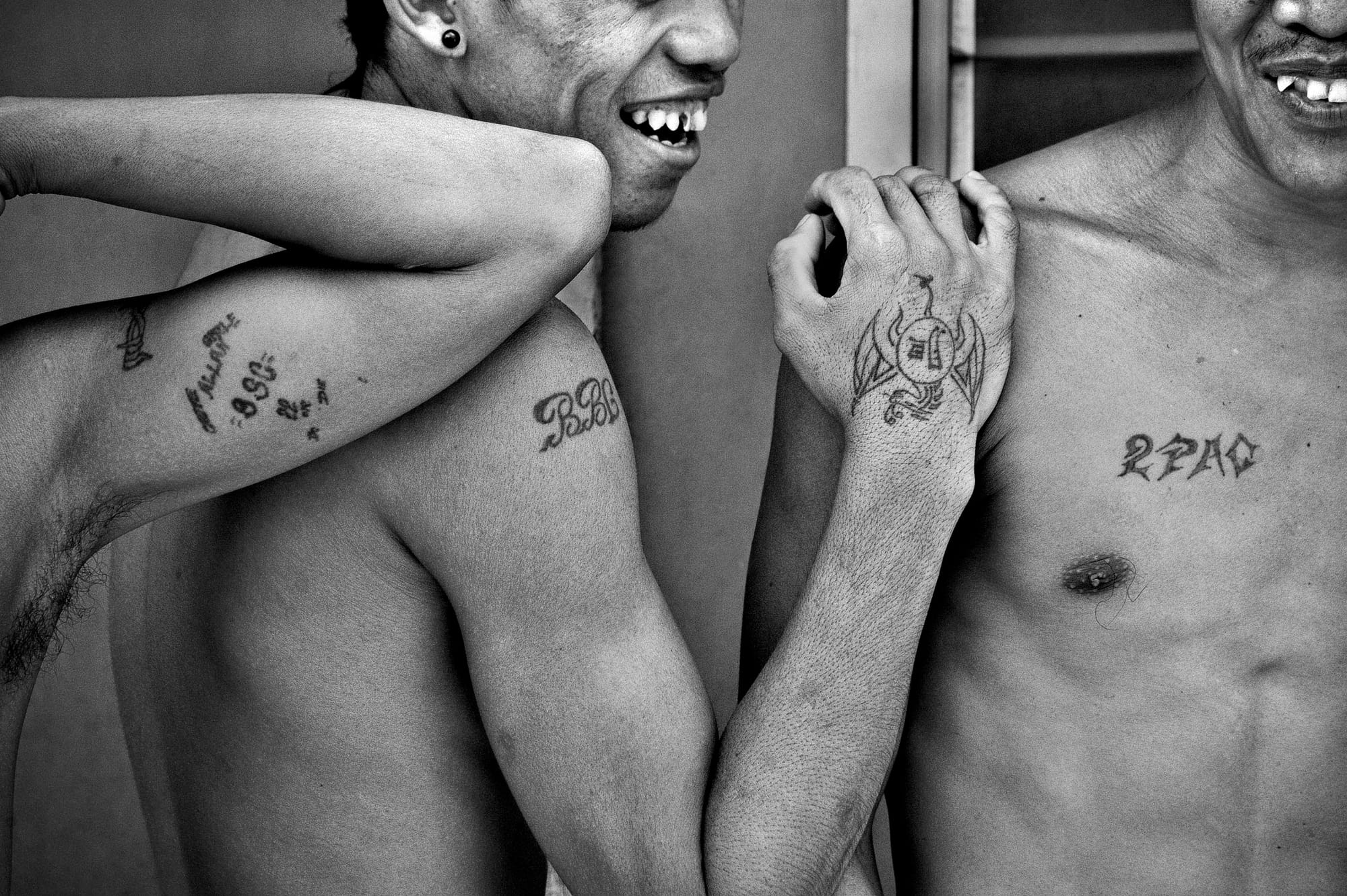

One of your most recent projects, Marked: The Gangs of Baseco, follows the lives of ex-gang members who are trying to reinvent themselves. How did this idea come to mind? Can you tell us more about this story?

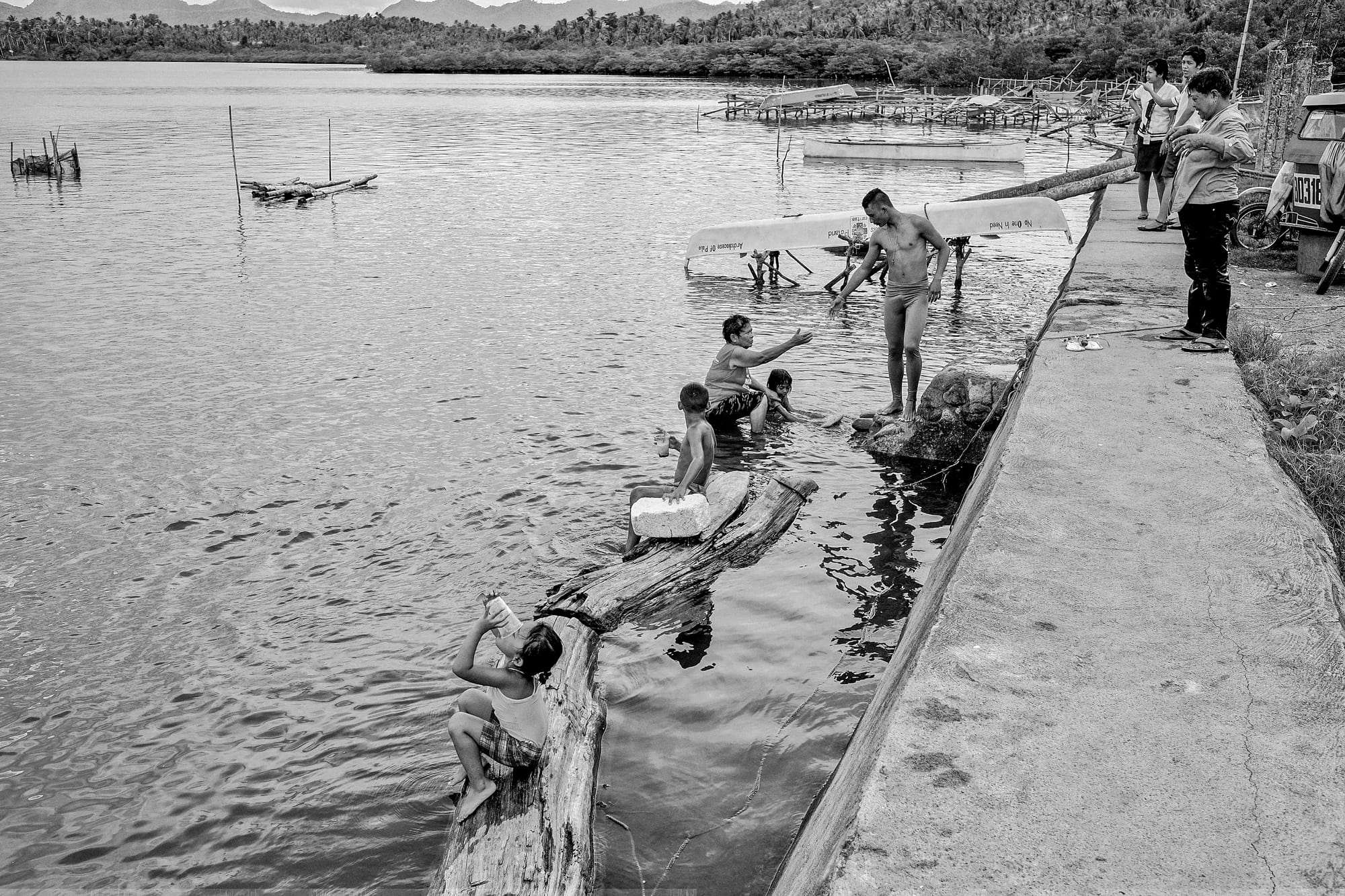

This was actually a while back, around 11 years ago, and my first foray into documentary photography. The area, BASECO compound, was one of the densest neighborhoods in Manila and also a microcosm of the majority of the issues the Filipinos face. I met the group back in 2006 and started to engage with them later that year. I was connected to them almost every day until late 2008 when I was able to come up with a stern selection of images that I felt reflected the lives of the former gang members. This project/story was a personal reflection on the established adage ‘how the other half lives,’ an essayist view on youth, counter culture and survival in a city with a widening marginal gap.

What were the main difficulties in getting the job done? And what has the reaction of people been? Talk us through the creative process behind Marked: The Gangs of Baseco.

The main difficulty was the access, every moment spent with the group was uncertain because they can always change their minds and bar me from their group. Other more personal issues are the never-ending question of representation, am I portraying them sensibly and humanely? Is my intimate manner adequate for people to empathize with them? With a very traditionalist documentarian approach in mind, I dived into this story with no end in sight. I just wanted to get to know the group better and widen my perspective on Filipino youth and how they live through the vicious life cycle in one of Manila’s most dangerous slums.

Who are your inspirations? What photographers do you look up to? And are there photographers from the Philippines that you believe deserve more attention?

I was molded by the traditional/classic documentarian approach so the names Smith, Bresson, Richards, Kouldelka amongst others would be part of my creative core. But also, I was very much influenced by Filipino masters of the documentary craft such as Soriano, Yabao, Gascon, Baluyut, Sepe, Gloyugo, Baldovino, Gacad, Jamir, etc… They have all been a source of positive pressure on how to get a better frame than yesterday. There are a lot more, and I'm pretty happy and proud that a project archiving the works of these great photographers are being archived and made available.

You've worked both on social documentaries but also published more conceptual books. Where do you draw the line between journalism and art? What does objectivity mean to you?

My main workflow still revolves on straight reportage and visual journalism. My ‘experimental’ pursuits in photography are usually for myself, as a means of expression or on how to take a body of work further photographically. Objectivity is essential and very much needed in this day and age of news fakery, but I think a photo essay will be boring and disengaging if it doesn’t take sides.

Your work has appeared on a significant number of publications worldwide. What would you suggest to a young photographer starting out, willing to get their work seen? Are there any tricks you've learned along the way?

No trickery nor shortcuts involved. I see that a lot of the younger photographers soar high and get works published in the top publications worldwide far faster than when we were starting out with the help of social media and different platforms that help them push their work out and get known. But brights lights and likes will fizzle while images that are produced with hard work will always find its way to be shown. Romanticism aside, I believe that work should always come first before pushing oneself out in the open. A rigor that is tried through critic in developing one’s voice is something that I always suggest to younger photographers who’s trying to pursue this craft.

© Veejay Villafranca

You often work with non-profit organizations. What does photography mean to you? What role does it play in the context of conflict?

Working with NGOs has been one of my primary sources of assignments for a few years. I like it because, at times, I get to be a bit more creative in approaching a story/issue. But at the same time, it is frustrating due to the long list of limitations while working with non-profits due to ethical and some out of date guidelines.

For me, photography is still one of the most effective modes of communication due to our brain’s mental ability to relate to images initially more than words. Photography to me is a reflection of another person’s reality that comes with great privilege (to life and history) but comes with a heavy responsibility in regards to representation and accuracy. In conflict photography, photography and visual journalism are still crucial in bearing witness to the atrocities brought by war and to remind us that they should not be repeated.

What issues do you see in photojournalism today?

Issues of dwindling assignments and lack of work are not new but still very much need to be discussed most especially to those working in developing nations. The more pressing issues of abuse by gatekeepers are being called out and talked about in the past years, but much has yet to be done to make the newsroom/institutions a safe place to work for all. Last, the issue of balance in representation and hiring more local photographer has been given attention as of late and needs to be further acted on.

Technical question: what's in your backpack? What do you shoot with more often?

Oh, that’s a good one. I have two camera bodies (Fuji xt2 and xt3), and my go-to lenses are the 23mm f1.4 and the 35mm f2.0. I normally carry just one body for personal shoots with a 23mm or 35mm. I also have a 35mm film rangefinder (Konica Hexar) at times when I feel the need to shoot film. I usually shoot with digital cameras and with my phone, but when I get serious on a subject, I make my film camera my primary tool.

Are you working on something new at the moment? What can we expect from you in the future?

After working with Signos (my first book), I am working on something about Filipino faith practices and religiosity. I started this project over 10 years ago and had no definite plans for it until recently. I’ll also continue working on assignments and collaborations in different parts of Asia.

© Veejay Villafranca